Introduction

The ranger has been a core class in D&D since April of 1975, when they were first published in The Strategic Review Vol 1, No. 2 (Summer, 1975), and has been an archetypal character type for even longer. Many consider Aragorn to be the quintessential ranger—a skilled warrior and leader, tracker and hunter, possesses healing powers, has an almost mystical kinship with animals, and knowledge in Middle Earth history, religion, mythology, and languages… opposing Aragorn, is the 5e Ranger Class, which has sparked a lot of controversy over the years, with two general critics being their mechanically unexciting or weak gameplay when compared to the other classes, and their lack of identity, as some seem to feel the 5e ranger does not feel appropriate for the archetype. Due to making this length of this paper already, I will only be addressing the latter claim, as the former deserves its own article. Despite the 5e ranger’s problems, I don’t believe identity is an issue with the ranger—I believe the only issue depends upon what one considers to be a ranger.

So I ask, what even is a ranger?

The word ranger can mean a lot of things, though some mistakenly believe that ranger refers to their use of “range weaponry” which is one reason why rangers often have range weaponry, usually bows or rifles depending on the setting. The term ranger actually doesn’t mean ‘one who fights from range,’ but ‘one who watches over a range’ such as a Park Ranger who watch over local and national parks—this feels appropriate as outdoorsmanship is a key quality of the ranger archetype.

The thing is, survival skills can be incredibly broad, ranging from various tier levels of tracking and hunting, to trap making, herbalism, stealth, and animal cultivation or kinship. Because survivalists have the mindset of being prepared for anything I think that bleeds into their fighting tactics, usually relying on ranged weapons to ambush targets, learning how to fight with melee weapons for versatility, setting traps, tracking down targets towards those traps, and practicing scouting. I think this is why rangers are sometimes seen as specialized or elite warriors, similar to earlier D&D editions that categorized rangers as special fighters (similar to the paladin) who has more abilities at the cost of Alignment flexibility. Let’s compare the controversial 5e ranger to the 2e ranger, a good comparison as 2e was the final iteration of the “old school era” of D&D, and I think it can help highlight some of the glaring reasons why I think people hate the 5e ranger.

2e vs. 5e

In 2e, rangers had no penalty when fighting with two weapons (as long as they wore nothing heavier than leather armor)—even though no well-known real or fictional rangers did this at the time. With the help of D&D’s icon Drizzt Do’Urden, the ranger would become synonymous with two-weapon fighting.

Additionally, rangers had enhanced sneaking skills, being able to move silently and hide in shadows like (but not better than) “thiefs” (now rogues in new school D&D).

All character classes have a penalty when attempting to track, except the ranger who became associated with tracking.

My least favorite ranger ability is their “Favorite Enemy” in which they had extensive knowledge, combat and tracking skills in finding one particular enemy, gaining a +4 on all attack and damage rolls, but the drawback was the ranger becoming aggressive towards your favorite enemy in combat—the specialized knowledge towards a specific type of creature is a cool, ranger-esk ability, but the forced anger feels like rail road role-playing (although ironically, the 5e ranger did this poorly too).

Rangers were also given some magical abilities, at 8th level they could cast a handful of plant or animal-based spells. As one can see, spellcasting was a feature, but not a core feature.

Finally, rangers had Animal Friendship, where domestic animals are friendly to you, and attacking animals are likely to be your friend—again, despite many being hunters, rangers seem to have some of the most respect for animals out of any group of people (perhaps just short of druids).

In order to play a ranger, your fighter had to have an extensive ability requirement, including a Strength and Dexterity of 13, and a Constitution and Wisdom of 14; additionally, rangers had to be of good alignment, their choice of Lawful, Neutral, or Chaotic. For comparison, 2e fighters had the benefit of not being restrained to a set ability score, could play any alignment including evil, could begin building fortresses and creating armies much sooner and better than the ranger or paladin, and could obtain weapon mastery over a single weapon at the expense of one or two (if a ranged weapon) weapon proficiency slots (which is essentially like if 5e had Expertise/double proficiency bonuses for weapon proficiencies)—it sounds cool, but considering how magic items were more plentiful and reliant upon in the older editions, so not having mastery wasn’t detrimental. Oftentimes, if you could play a ranger or paladin, you usually did.

5th edition really changed rangers, who went from being elite fighters to being more of their own thing.

Rangers can sometimes be classified as elite fighters, but a generalization would do many rangers and fighters a disservice—there are plenty of incredible real and fictional fighters archetypal individuals that wouldn’t be classified as rangers. Starting in 3e, rangers and fighters became their own separate classes, but rangers were still considered high damage dealing combatants. For 5e, Wizards of the Coast (WotC) wanted more distinguish fighters and rangers, this is where the infamous belief of 5e rangers being a culmination of fighters, rogues, and druids.

Like fighters, rangers have proficiency with all weapons, shield, and armor (except rangers don’t get heavy armor), similar fighting style selections, a high d10 Hitdice, and general martial combat usage.

Like rogues, rangers have great stealth capabilities, although this is differentiated as rogues have Cunning Action and often times expertise in stealth skills, whereas rangers will have magical abilities and similar rogue abilities at higher levels. What often goes unmentioned is the rangers use of Intelligence, much like a rogue. At level 1, rangers gain two abilities, their choice between Favorite Enemy and Favorite Foe, and then either Natural Explorer or Deft Explorer. Regardless of which pair of abilities are picked, rangers will have bonuses to some checks involving any of the five Intelligent skills. Despite two of their core abilities heavy use of Intelligence in their core, archetype defining abilities, this often goes unnoticed because of their reliant of Wisdom for it’s association with survival, animals, medicine… nearly everything rangers are good at, as their secondary ability to Dexterity.

Finally, rangers are more similar to druids in 5e than any previous edition. As was the case in 2e, D&D rangers have always received spellcasting of some type, picked up along the way during their travels; but now, rangers are part of the trio of half-casters (rangers, paladins, and artificer), martial classes that gain spell levels at half the rate as normal spell casters. Rangers are similar to druids as they use Wisdom, Nature-based spell casting, and the two share many spells. The ranger as “half-caster, half-martial” concept perhaps more than any other distinguishes the 5e ranger, and where most critics draw the line. Because they possess magical abilities like the druid (although, ranger magic will always be weaker than a full-caster), rangers are balanced by design to be less powerful in combat than a fighter—completely eliminating the common trope of rangers being elite soldiers.

Rangers level 1 core trait Favorite Foe functions similarly to a spell (it’s concentration but a free action to “cast”) as you mystically turn a single creature you hit with an attack that you can see into your Favorite Enemy. The 5e ranger more than most other ranger depictions emphasis the ranger as “half-spellcaster and half-martial” as their spells and abilities are interwoven between the more grounded and the fantastic. At 2nd level, rangers learn both a fighting style (emphasizing their martial warrior aspect) and learn spellcasting (emphasizing their fantastic, spellcaster side); however, a fighting style exclusive to rangers is the Druidic Fighting style which grants the ranger two Druid cantrips of their choice, again shifting the ranger towards the fantastic. Their spellcasting goes upwards to learning level 5 spells at 17th level, though the most common spells will be their strong variety of level 1 spells, such as hunter’s mark, goodberry, zephyra strike, entanglement, and absorb elements. At 3rd level, rangers gain a subclass, many of which lean towards the fantastic, such as the popular and powerful Gloom Stalker, a more fantastic version of the 2e “Stalker” kit, a subarchetype where the ranger’s survival and warrior qualities lean more towards spying, infiltration, and assassination. The 5e Gloom Stalker emphasizes 5e’s high magic setting by granting them enhanced darkvision and invisibility in shadows.

The Guardian and the Solider

Rangers became, either by design or accident, associated more in 5e as a high fantasy Forest Ranger, who I refer to as the Guardian subtype, to oppose the Solider subtype. What I call the Guardian subtype refers to rangers who are not enlisted into some form of military, agency, or even religion, such as the Rangers of the North and South, the Ranger Corps of Araluen, and The Tribe/The Children of the Watch respectively. The Guardian subtype comes from the Forest Ranger trope, who aren’t the normal uniform selves but rather a forest (and other terrains) dwelling recluse, who is a self-appointed guardian of an ancient/enchanted land; interestingly, there was a 2e ranger kit (comparatively to 5e, a subclass except it had more strict requirements) represented this archetype perfectly in its name “the Guardian.”

The Fantastic and Realism

Because there is an important distinction between the Guardian and the Solider, but also the inclusion of magic to combat more grounded depictions of rangers, I have decided to a compare how grounded in reality each ranger is by broadly measuring on a spectrum between the Fantastic and Realism. The Fantastic refers to anything dealing with magic or the supernatural, or metaphysical and physics defying stunts, whereas Realism refers to the accurate, detailed, unembellished depiction of nature or of contemporary life.

In short, the Solider to Guardian scale measure the rangers role in society, whereas the Fantastic to Realism scale measures the rangers traits and abilities in regard to their settings nature.

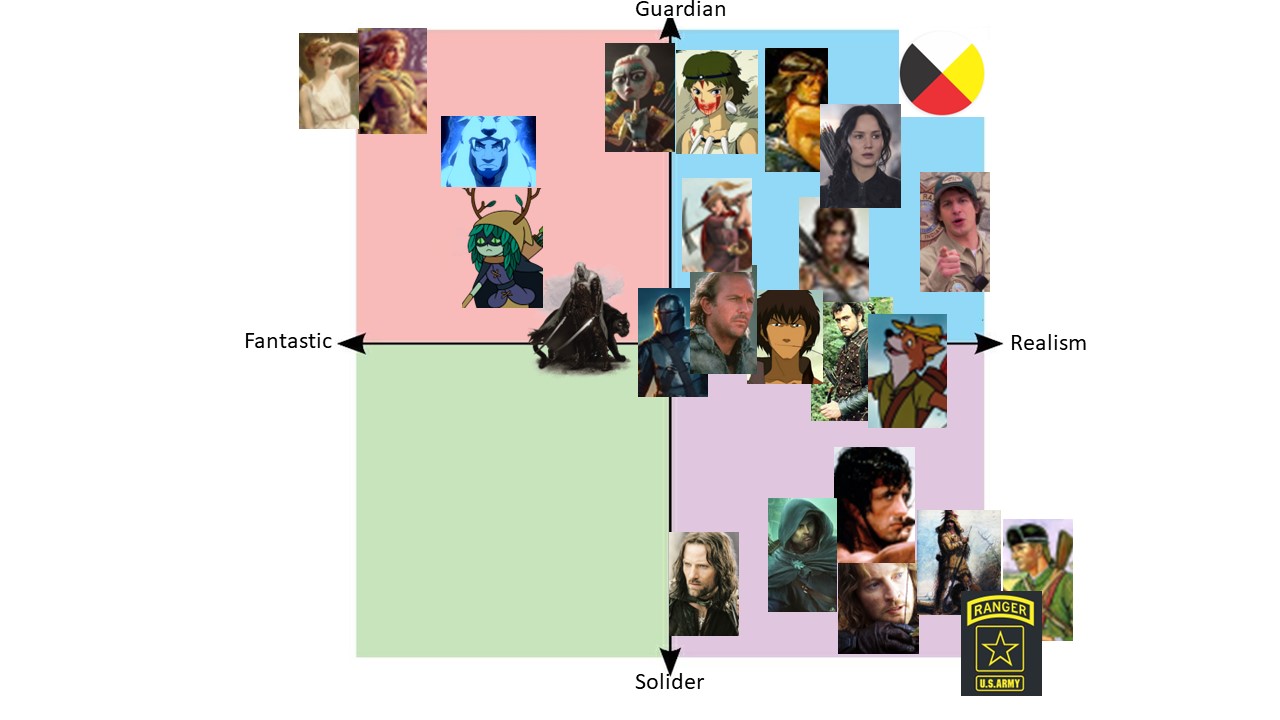

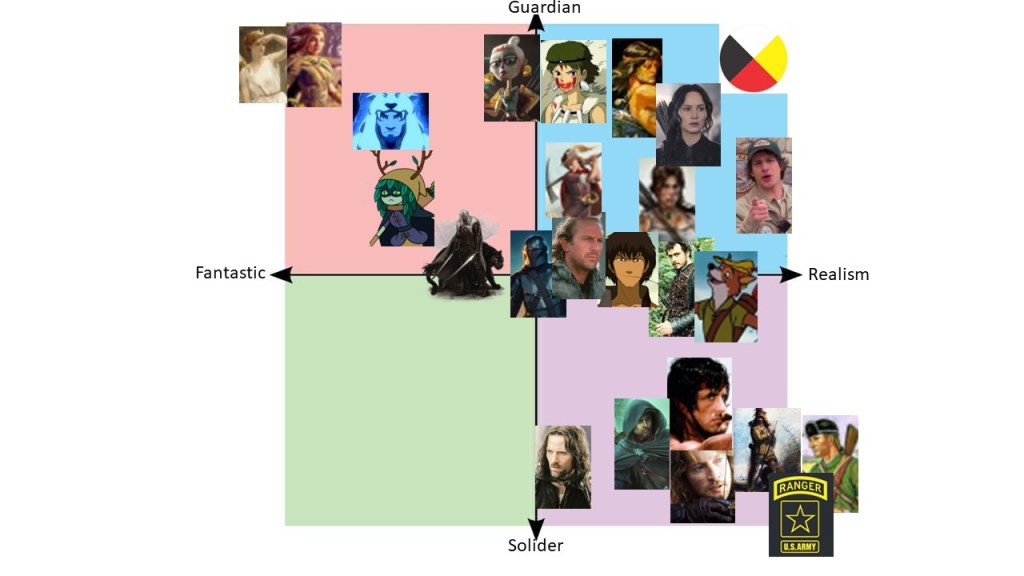

The Ranger Subtype Scale

The ranger archetype is more broadly defined as:

- 1. Rangers are warriors; they are fighting for a (just) cause.

- 2. Rangers are survivalists; they are comfortable in the wilderness.

The ranger subtypes can be more narrowly charted between the characters role in relation to society, and the characters traits and abilities in relation to their setting.

- 1. Relation to Society

- Soldiers are those who are apart of the military, government agencies, or similar organized groups.

- Guardians are wilderness dwelling recluses and/or protector of a land or people.

- 2. Relation to the Universe

- The Fantastic refers to those who utilize magical or supernatural abilities.

- Realism refers to those whose abilities are more grounded in reality.

The ranger subtypes defined:

- X-axis: Fantastic → Realism

- Y-axis: Guardian ↓ Solider

5e Rangers Identity

As anyone can see, the mainly well known rangers I listed tend to follow a curved pattern towards Realism-Solider, Realism-Guardian, and Fantastic-Guardian sections of the graph, whereas the Fantastic-Solider is virtually empty. On the other hand, however, the 5e ranger was intentionally designed in a way to lean more towards the fantastic as the player levels up, and naturally that leads so much potential for the less explored Fantastic-Solider subtype to be explored.

Because rangers in 5e use so much magic, I can’t help be see why some are iterated with their identity, as it doesn’t form to the viewer’s concept of a ranger, in this case, the Realism-Solider. I have a suspicion that some view the 5e Ranger as wrongly portraying the ranger archetype, but I think it’s more so that the ranger leans towards the Fantastic. To some, a ranger should be the hunter’s mark as in, they have the abilities to find and hurt their target, as opposed to having to cast a spell. I can’t help but think that some feel like spellcasting or at least too much spellcasting takes away something from rangers, but really I think its just an unexplored territory for rangers as a literary and game design character archetype.

Conclusion

Personally, I like the 5e interpretation of the Ranger. I’ve played 5e extensively and quite a bit of 2e, and in my experience old school editions had a more “sword and sorcery” feel where death loomed around every corner, and most of your strengths as you level up become more reliant from magical items and how you use them between you and your party. 5e in particular feels like playing a high fantasy superhero, in great part due to the high fantastical setting where magic is imbued into everything. Level 1 characters remind me of My Hero Academia season 1 when Class-1A all had great potential despite being new to heroing. The half-casting ranger feels completely appropriate when you consider the high fantasy world they must adopt to, making them feel true to their defined archetype, even if they lean towards the less charted Fantastic-Solider.

In a future post I’ll explore if the 5e rangers core traits are truly too weak in terms of mechanics.